Here are some interesting high-level facts about the “what” and “where” pathways in vision. Multiple people in this audience probably already know a lot of this, but it might be a useful refresher.

I got a lot of this from the textbook “Basic Vision: An Introduction to Visual Perception”.

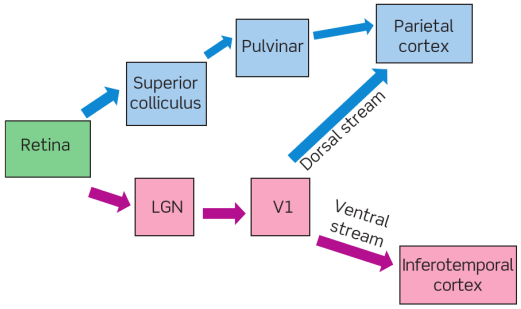

A diagram

The ‘what’ (pink) and ‘where’ (blue) pathways are pictured below. Note that there are two pathways to the parietal cortex – one goes through the LGN, and the other through the pulvinar. (Both of these are nuclei of the thalamus.)

EDIT: This diagram is from the textbook, and it oversimplifies a little bit. A couple notes:

- The Pulvinar also receives input from V1. V1 -> Pulvinar -> V2 is likely the “main” feedforward pathway in our current theoretical thinking

- When it says “parietal cortex”, It’s referring specifically to the Posterior Parietal Cortex.

Thanks @ycui for pointing these out.

Experiments with simple objects

Here’s a simple experiment that illuminates the “what” pathway. Show a monkey two objects, one with food underneath it. A monkey will quickly learn if the food is always underneath, say, the cylinder.

When a monkey has a lesion in the anterior part of inferotemporal cortex (area TE), it will never learn that the food is always under one object. It can’t use the simple shape information “cyllinder” vs. “cube” to learn the task.

A monkey with a lesion in the ‘where’ pathway can handle that task just fine. Here’s a different experiment. Show a monkey two food wells, and put food in only one of them. Place an object nearer to the well that has the food.

A monkey with a lesion in the posterior parietal cortex will never learn to go to the food well that’s nearer to the object. It seems it can’t use information about the location of things. (Mishkin et al., 1983: Object vision and spatial vision: two cortical pathways)

What happens when you have ‘where’ but not ‘what’?

If your V1 is removed, you will think you’re blind, but you’ll still be able to use information from vision. The term for this is blindsight.

Here’s a monkey experiment. Place a target in one of two locations, and have the monkey indicate where the target appeared. If the monkey’s V1 is removed… it can still do this. It’s almost as good as a normal monkey.

Here’s another monkey experiment. Have the monkey simply indicate whether a target is present. If the monkey’s V1 is removed, it can’t do this. So it’s like the monkey doesn’t know whether a target is there, but if asked it will guess correctly where it is.

It’s interesting: from the outside, it can be hard to tell when a monkey has no V1. For the monkey, the experience is literally night and day, but its performance in many experiments is unaffected.

Now let’s go one step downstream. If your V1 is functioning, but your inferotemporal cortex is damaged, you’ll have visual awareness, but recognizing objects will be very difficult. Here’s an interesting experiment with patient DF. She’s shown a slot, and she’s asked to indicate its orientation. She can’t do it, her guesses are close to random. Then she’s asked to post a letter through the slot, and… she can do it. She’s just as good at this as a normal person.

…and if you have ‘what’ but not ‘where’?

The term for this is optic ataxia. A classic study: a patient with optic ataxia can accurately report the orientation of a slit in a target, but is unable to post a letter through the slit. (Perenin and Vighetto, 1988, Optic ataxia: a specific disruption in visuomotor mechanisms)

Another story: A patient had a tumor in her right parietal cortex. She has to put her left hand through a slot. If the slot is in her left visual field, she’s unable to orient her hand properly for the slot. If it’s in her right visual field, she can.

‘What’ and ‘How’

It might be useful to think of the second pathway as the ‘How’ pathway, not the ‘Where’ pathway. Milner and Goodale proposed this theory on the basis that “people with damage to the dorsal stream could see things fine – they clearly have visual awareness or visual consciousness – but they can’t act on this information”. (quote from Basic Vision textbook) (Milner, Goodale, 1995: The Visual Brain in Action)